Introduction

The term "comfort women" refers to women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial

Japanese Army before and during World War II. This tragic chapter in history affected thousands of women

across Asia.

Context

The comfort women system was established during the 1930s and lasted until the end of World War II in 1945.

The Japanese military employed a variety of tactics to enslave Asian women, including kidnapping, coercion,

and false promises of employment. These women and girls were forced into "comfort stations," military

brothels where they were subjected to daily sexual servitude from morning to late evening. Conditions were

harsh, with overcrowded rooms lacking basic amenities like bedding, electricity, and adequate food. As the

military moved, so did the women, with little regard for their health or safety.

On average, a comfort woman was forced to serve up to 20 soldiers a day, with some servicing as many as 50.

Soldiers were free to abuse the women physically and sexually, and while they were nominally required to pay

for services, it is highly unlikely that the women received any portion of the payment. The women were

rarely allowed time off and were strictly forbidden from leaving the comfort stations.

Of the Korean survivors who have come forward, only a dozen are still alive today. Many others may be alive

but choose to keep their experiences private.

A Guide to Understanding the History of the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue

This article is to help understand the history of the 'Comfort Women'.

Voices of the Survivors

To better understand the experiences of comfort women, here are firsthand accounts from survivors.

This account comes from a South Korean survivor, Kimiko Kaneda, from a video

produced by the AWF, 1998:

"My father

When I was 14 years old, my father was arrested by police because he did not visit Japanese

shrines. I was

busy caring for my younger brothers and keeping the house, and had no idea of going to

My father could

speak Japanese well and told a lie that from now on he was going to visit Japanese shrines

with his followers. Liberated, he went home. He cured the burn on his leg which the police inflicted. Then

the police came to arrest him again. It was 4 o'clock in the morning. Father was praying in the church. I

sprang up and ran to the

"Daddy, run away. The police are here again." At that time around the church

was surrounded by rice fields

and vegetable fields. Close by was a Japanese village. He stopped praying and fled through the Japanese

village. He went through Taegu and arrived at Sengju to see his aunt, who hid him from police.

In China

At 4 o'clock in the morning we took ride on a train. It stopped for two hours at Shanhaiguan at which point

myself and Yoshiko attempted to escape. But the exits were blocked by military police. We were much too

scared to escape from the train. We spent one night in the train and on the second day arrived at Tianjin at

11 o'clock. When we got off the train at Tianjin, fully armed soldiers were waiting for us with a truck, a

coach and a jeep. We were put on the coach and taken to Peitan.

In Peitan we got off the coach and entered a house, in which a number of women and girls were crowded. Near

the house there was garrison of a Japanese regiment, which was always patrolling for enemies. On that day we

were divided into groups of ten and I was sent with other girls to Zaoqiang. There, in a city surrounded by

walls, was a unit of the Japanese army stationed. We were taken to the dining room of the unit and made to

sit on the floor.

Forced to become a comfort woman

How did I feel? I felt as if we were taken here to be killed. I could not but weep. No one talked. All were

weeping. That night we slept there and in the morning we were put in those rooms. Soldiers came to my room,

but I resisted with all my might. The first soldier wasn't drunk and when he tried to rip my clothes off, I

shouted "No!" and he left. The second soldier was drunk. He waved a knife at me and threatened to kill me if

I didn't do what he said. But I didn't care if I died, and in the end he stabbed me. Here( She pointed her

chest).

He was taken away by the military police and I was taken to the infirmary. My clothes were soaked with

blood. I was treated in the infirmary for twenty days. I was sent back to my room. A soldier who had just

returned from the fighting came in. Thanks to the treatment my wound was much improved, but I had a plaster

on my chest.

Despite that the soldier attacked me, and when I wouldn't do what he said, he seized my wrists and threw me

out of the room. My wrists were broken, and they are still very weak. Here was broken.... There's no bone

here. I was kicked by a soldier here. It took the skin right off... you could see the bone.

In the comfort station in Shijiazhuang

When the soldiers came back from the battlefields, as many as 20 men would come to my room from early

morning. That's why I had to have a hysterectomy (in my twenties). They rounded up little girls still in

school. Their genitals were still underdeveloped, so they became torn and infected. There was no medicine

except something to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and Mercurochrome. They got sick, their sores

became septic, but there was no treatment.

The soldiers made Chinese laborers lay straw in the trenches and the girls were put in there. There was no

bedding... underneath was earth. There was no electricity at that time, only oil lamps, but they weren't

even given a lamp. They cried in the dark "Mummy, it hurts! Mummy, I'm hungry!" We wanted to go and give

them our leftover food, but there were a lot of sick and disturbed people in the trenches. Some of them had

TB. I was scared they might pull me in to the trenches, and I didn't want to go there. I could have gone if

I had a lamp.

When someone died the girls got scared and began to cry. Then everyone in the trenches was poisoned and they

closed up the trench. They dug another trench next to it.

With dying soldiers

Hundreds of soldiers were killed or injured everyday. They put out boards on the parade ground and erected

tents over them. The dead were put in there. They laid out the injured there. The soldiers cried out in

pain. We didnft give water to those who still had the will to live. We wiped their lips with a cloth soaked

in alcohol, and gave them an injection to make them sleep. We gave two injections to the seriously wounded.

After the morphine shot they would stop crying and sleep. When the morphine began to wear off they would

grab at my clothes. They usually called me Kaneda Kimiko, but at those times they would call me Onesan

(sister). "Onesan, please give me another shot!" I felt sorry for them, so I would inject them again, and

they would sleep.

When they were dying, not one soldier said "Tenno Heika Banzai". They would look at pictures of their

mothers or their wives, and say, weeping, "Mother, I may die. If I die, let us meet again at Yasukuni

Shrine". I also wept at these scenes.

I thought Yasukuni Shrine must be a wonderful place. The soldiers said that they would go to 'the place

beneath the blossoms' at Yasukuni. I went there, but there was nothing, only white pigeons. I sat down

there, thinking without uttering voices. Soldiers said that they would go to 'the place beneath the

blossoms' at Yasukuni, but now their spirits of enmity turned into the pigeons around me. My heart was

broken. I bought bait for the pigeons at an automat. The pigeons came to my hands and picked at the bait.

Another account comes from a Filipino survivor, Maria Rosa Henson:

"I was forced to stay at the hospital which they have made as a garrison. I met six women in the garrison

after two or three days in the place. The Japanese soldiers were forcing me to have sex with several of

their colleagues. Sometimes 12 soldiers would force me to have sex with them and then they would allow me to

rest for a while, then about 12 soldiers would have sex with me again.

There was no rest, they had sex with me every minute. That's why we were very tired. They would allow you to

rest only when all of them have already finished. Maybe, because we were seven women in the garrison, there

were a fewer number of soldiers for each one of us.

But then, due to my tender age, it was a painful experience for me. I stayed for three months in that place

after which I was brought to a rice mill also here in Angeles. It was nighttime when we were fetched to be

transferred. When I arrived in the rice mill, the same experience happened to us. Sometimes in the morning

and sometimes in the evening... not only 20 times. At times, we would be brought to some quarters or houses

of the Japanese. I remembered the Pamintuan Historical House. We were brought there several times. You

cannot say no as they will definitely kill you. During the mornings, you have a guard. You are free to roam

around the garrison, but you cannot get out. I could not even talk to my fellow women two of whom I believed

were Chinese. The others I thought were also from Pampanga. But then, we were not allowed to talk to each

other.

Many have asked me whether I am still angry with the Japanese. Maybe it helped that I have faith. I had

learned to accept suffering. I also learned to forgive. If Jesus Christ could forgive those who crucified

Him, I thought I could also find it in my heart to forgive those who had abused me. Half a century had

passed. Maybe my anger and resentment were no longer as fresh. Telling my story has made it easier for me to

be reconciled with the past. But I am still hoping to see justice done before I die."

The third account comes from a Taiwanese survivor, who kept her identity private:

"At that time, my fiancée had been drafted by the Japanese military and sent to the south. I was helping my

father's business at home. One day, the Japanese police called and told me to come because they had a job

for me. They said that I would be preparing meals and mending torn clothes for the soldiers. I did not want

to go, but the police said that all men and women must come because the country was at war then and that

everybody must follow the General National Mobilization Law. So I went to work. I saw many Japanese

soldiers. There were some other women like me, too. We got up in the morning, washed our faces and cooked

breakfast to feed the soldiers. We washed their clothes and mended torn clothes. Then, at night, we were

called and confined to a room. ...it was a terrible job. I was only weeping. In the daytime I sewed clothes

and did the soldiers' laundry. It was easy. But at night I died. I was dying. I felt as if I was dead. I

wished to flee away, but I did not know the way. Soldiers were standing at the gates. If you fled, you would

be shot. I was too young. I did not know anything. I could not realize that I was pregnant. I began to throw

up what I had eaten. Then a woman, who was with me, said that I was pregnant. In two months I had a

miscarriage. Even now when I think about it, tears come to my eyes. Oh... I am sorry to make you hear such a

terrible story.

I thought that my fiance had died, but long after the war he returned unexpectedly. We

married. I could not tell that story to him. I have never told it to anyone. How can you tell such a

thing?

50 years passed. I came to know that there are people who had endured the same experiences. And I

could not keep silent. I could not bear it any more. I told my husband. I bowed and begged him to forgive

me. He was surprised and said that he had painful experiences during war, but you had also such painful

experiences. There was nothing we can do about it. That was the war. Saying such, he forgave me. Hitherto I

had always feared what my husband would do on knowing this story. I have thought and thought only about it.

When I told this to my husband, I felt at ease.

Now I am living with my husband, only the two of us. I can not work any more in farm, because I have pains

in my knees. I grow vegetables a little and go to sell them. As we are old, we do not eat rice much. So we

can live in this way. But we have no money. Our life is so hard."

Survivors

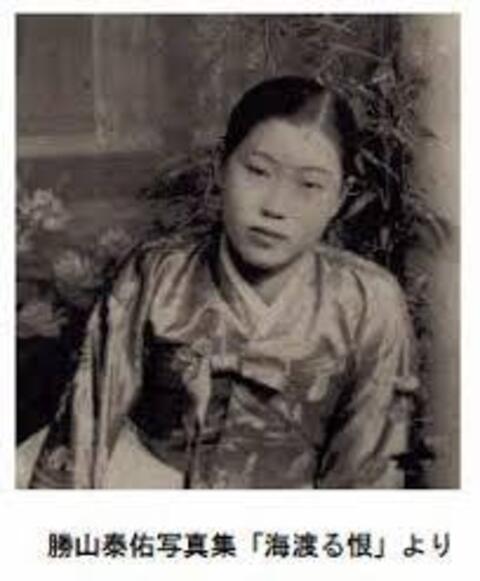

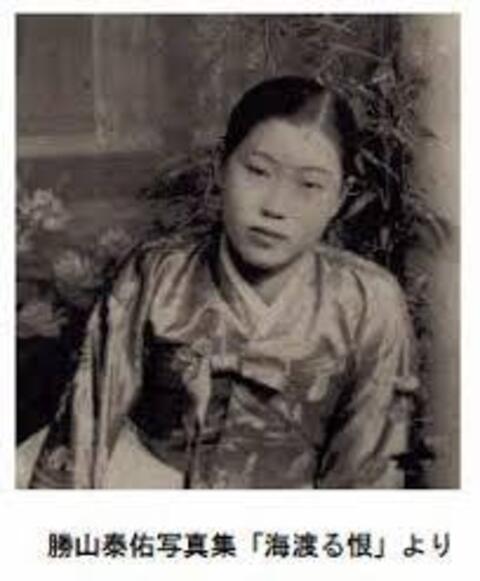

Kimiko Kaneda (South Korea)

Kimiko Kaneda, born in Tokyo in 1921, was the child of a Korean father and a Japanese mother. Shortly after

her birth, she was sent to live with her father's relatives in Korea. Her father, a priest, was eventually

arrested for disrespecting Japanese shrines. At sixteen, Kaneda moved to Seoul seeking better employment.

There, she was tricked by a Japanese man and forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military. Known as

Kimiko Kaneda, she was transported to various locations in China, including Tianjin, Zaoqiang, and

Shijiazhuang. Kaneda's childhood was marked by hardship and loneliness. To cope with her traumatic

experiences, she became addicted to opium. After the war, she underwent a hysterectomy and returned to

Korea. In 1997, Kaneda became one of the first recipients of reparations from the Asian Women's Fund (AWF)

in South Korea. She passed away in 2005.

Maria Rosa Henson (Philippines)

Maria Rosa L. Henson was born in Pasay City in 1927. The daughter of a landowner and his housemaid, she was

forced to endure sexual violence by Japanese soldiers during the occupation of the Philippines.

At fourteen, Henson was raped by Japanese soldiers while gathering firewood. She later joined the

HUKBALAHAP, an anti-Japanese guerrilla group, driven by anger towards her abusers. In 1943, she was captured

and forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military.

After nine months of captivity, Henson was rescued by guerrillas. Following Japan's surrender, she married a

Filipino soldier but later lost her husband to the communist army. Henson worked as a charwoman and factory

worker.

In 1992, inspired by a radio program, she became the first Filipina woman to publicly share her experiences

as a comfort woman. Henson was one of the initial recipients of reparations from the Asian Women's Fund in

1996 and passed away in 1997.

Global Acknowledgment and Apologies

Over the years, the international community has recognized the suffering of comfort women. However, multiple

reports reveal that the Japanese Education Ministry has purposely edited educational textbooks on World War

II to “water down” or even erase their actions during the period entirely. Officials have evaded

accountability by claiming the comfort women system never even happened—more recently, official Japanese

reports depicted the women as willful recruits for prostitution, denying that their military utilized any

form of coercion.